Tiger Dreaming

Imagining Alternative Histories

If images of the tiger hunt both perpetuated the empire and portended its fall, the history of British colonialism in India appears contained, even complete, within these objects. But the logic and legacy of imperialism remain alive, both in the violent hierarchies naturalized within these artifacts and their static position in the archive. The Victorian tendency to acquire, accumulate, and arrange knowledge––manifesting so prominently in the imperial museum––figures the archive as a tomb that determines the present and future as proceeding from the unchangeable past. It encourages us to forget that to write history is a subjective act.

To imagine alternative histories, then, resists this uncritical tendency to frame our current world as neutral, inert, and inevitable. It encourages us to see in the archive what Jacques Derrida terms “a promise” and “responsibility for tomorrow.” These historical imaginaries enable what was and what could have been to coalesce around the hope of what may yet be. Within the tiger hunts of the past, what possible worlds can we dream into becoming?

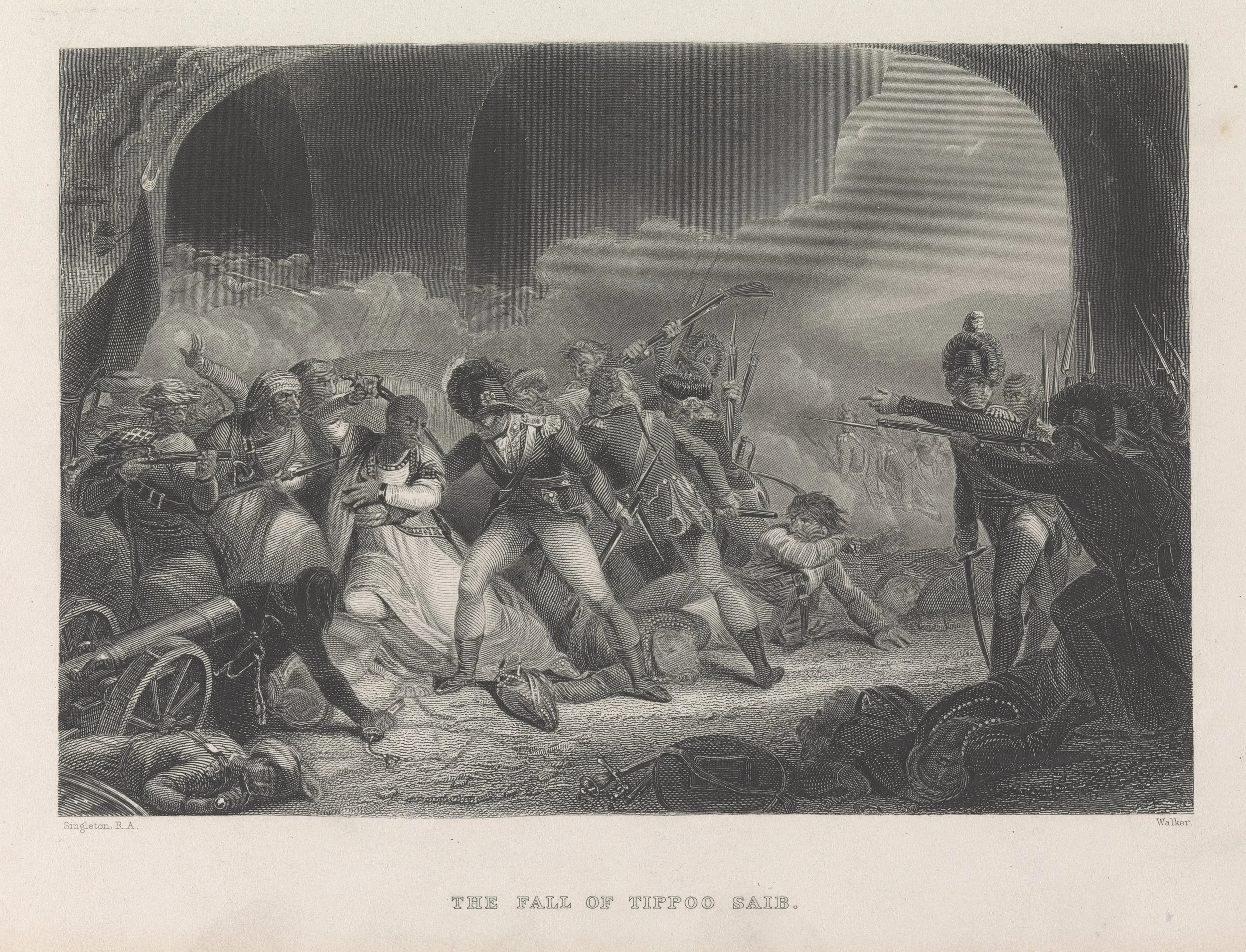

This section focuses on an alternative history centered around the Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan, whose seemingly singular resistance to British imperialism continues to be manifested and mythologized in the material and symbolic existence of Tippoo’s Tiger in and beyond the East India House today. History is written by the victors. What becomes of empire in a world where it was the Tiger of Mysore who claimed that privilege in 1799? What if “Tippoo Saib” had never fallen?

Walker, after Henry Singleton. The Fall of Tippoo Saib, n.d. Gift of Frank de Caro and Rosan Augusta Jordan. Yale Center for British Art

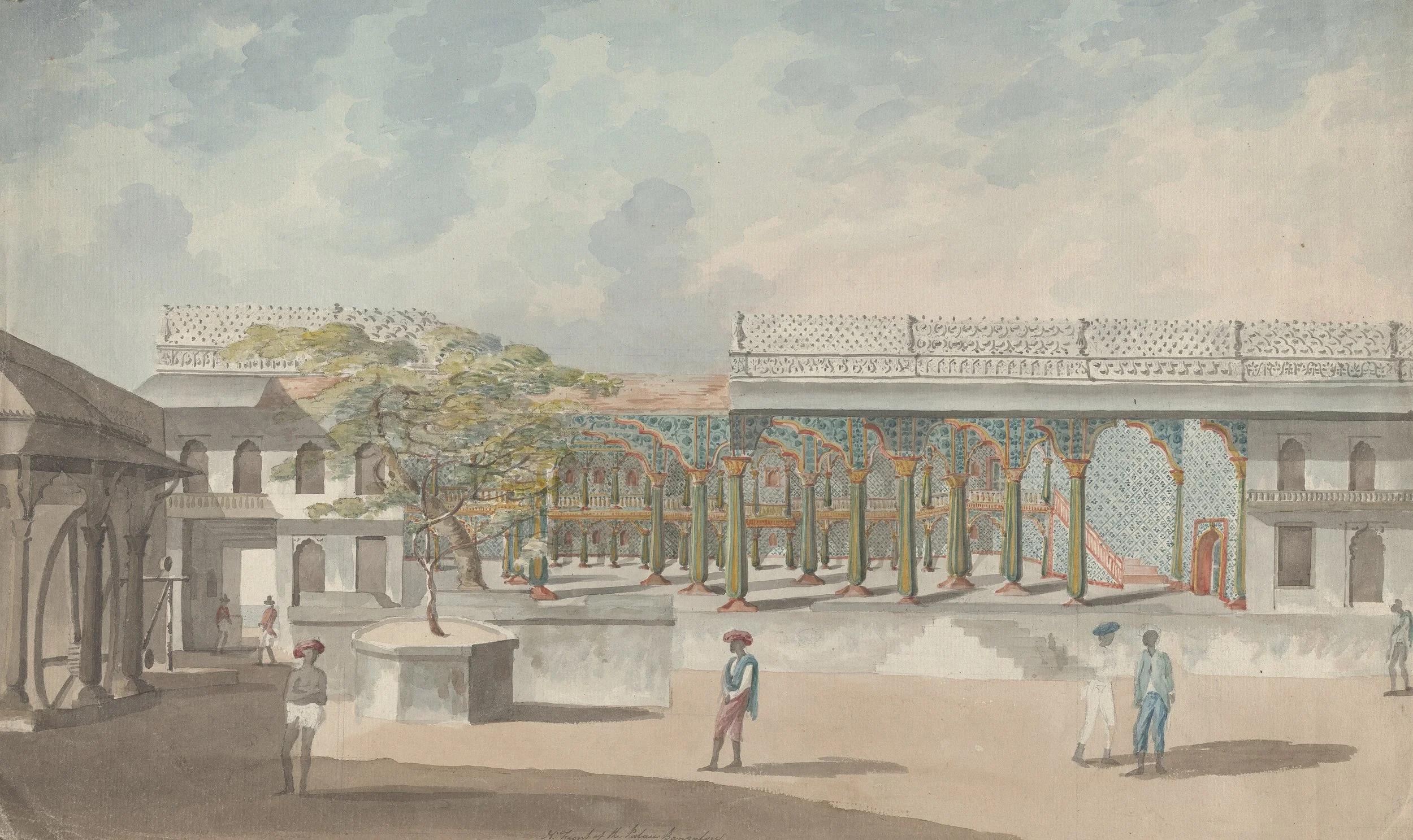

Lieutenant James Hunter. Tipu Sultan’s Summer Palace, 1792. Prints and Drawings, Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

D’Oyly’s and Tipu’s residences offer significant contrasts. This composition retains the English colonial presence, but the soldiers’ diminished scale opens new dynamics: the foregrounded locals claim authority in Tipu Sultan’s India.

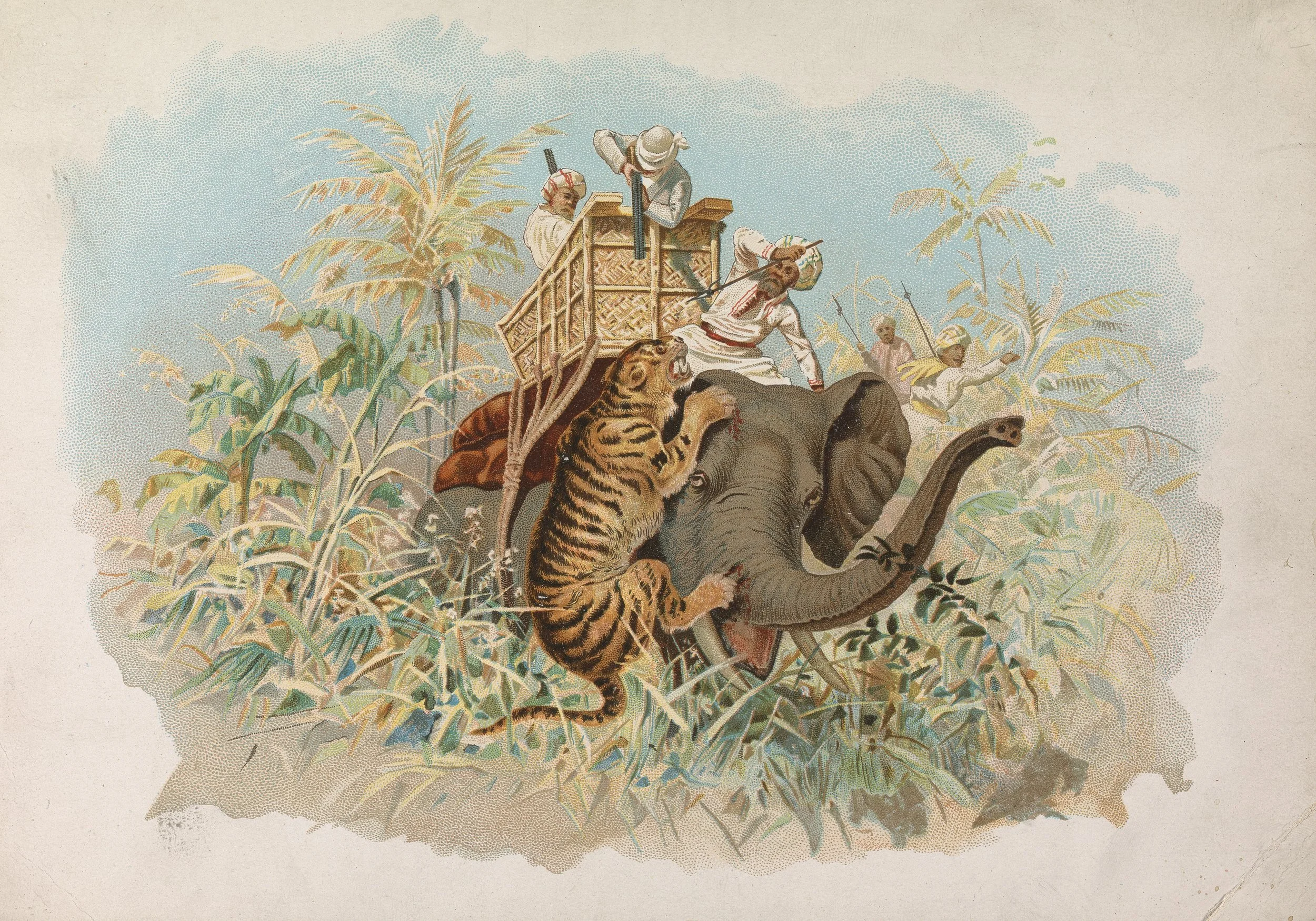

Situating this print in an imagined reality where the British never gained complete control over India, its already ambivalent representation of human-tiger power dynamics is amplified as a speculative site.

The tiger might embody Tipu Sultan’s indefatigable fight against the British (though ironically, Tipu, too, was not indigenous to the Mysore he ruled), but its central and successful mauling of the elephant render the hunt’s outcome uncertain. Simultaneously, the stippling makes emotions and clothing difficult to parse. The gunman’s obscured face generates ethnic ambiguity. The figures resist being ascribed a race-based cowardice.

Instead, the vibrant heroism evoked encourages us to imagine their individual contributions. Rethinking colonial images in this way highlights history’s omissions. In archival scholar Saidiya Hartman’s words, it attempts “to displace the received or authorized account.”

John Charlton. Tiger Hunting, n.d. Gift of Frank de Caro and Rosan Augusta Jordan. Yale Center for British Art

Mark Wood. A review of the origin, progress, and result of the decisive war with the late Tippoo Sultaun, in Mysore…[2d ed] London: L. Hansard for T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, 1800. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

In his wartime account, Mark Wood describes Tippoo’s Tiger as a “characteristic emblem of [Tipu Sultan’s] ferocious animosity.” Had the outcomes on the battlefield been reversed, we might today remember how Tippoo’s Tiger embodied India’s ruthless military might over the pathetic insubordination of the British. But this alternative history retains the framework of imperial domination. We must create more emancipatory forms of resistance in the archive.