Tiger Afterlives

Decolonizing the Archive?

In the strictest sense, it is impossible to decolonize the archive through intellectual work alone. As long as Yale University stands on the lands of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, and the Quinnipiac and other Algonquian speaking peoples, any engagement with university collections remains settler-colonialist.

But it is possible to activate the archive towards a future in which decoloniality is realized. One must, as the archival scholar Gil Z. Hochberg tells us, “rewrite, expand, circulate, and alter the archival conditions that currently limit our political imagination.” Current socio-political frameworks are rendered unchangeable through the archive’s preservation of linear time. Our counterfactual world of Tipu Sultan’s victory remains limited in its transformation of empire because this imaginary operates within narrative history. The disruption of the archive towards an equitable future, then, requires a reimagining that fosters radical solidarities beyond the limits of imperial time and space.

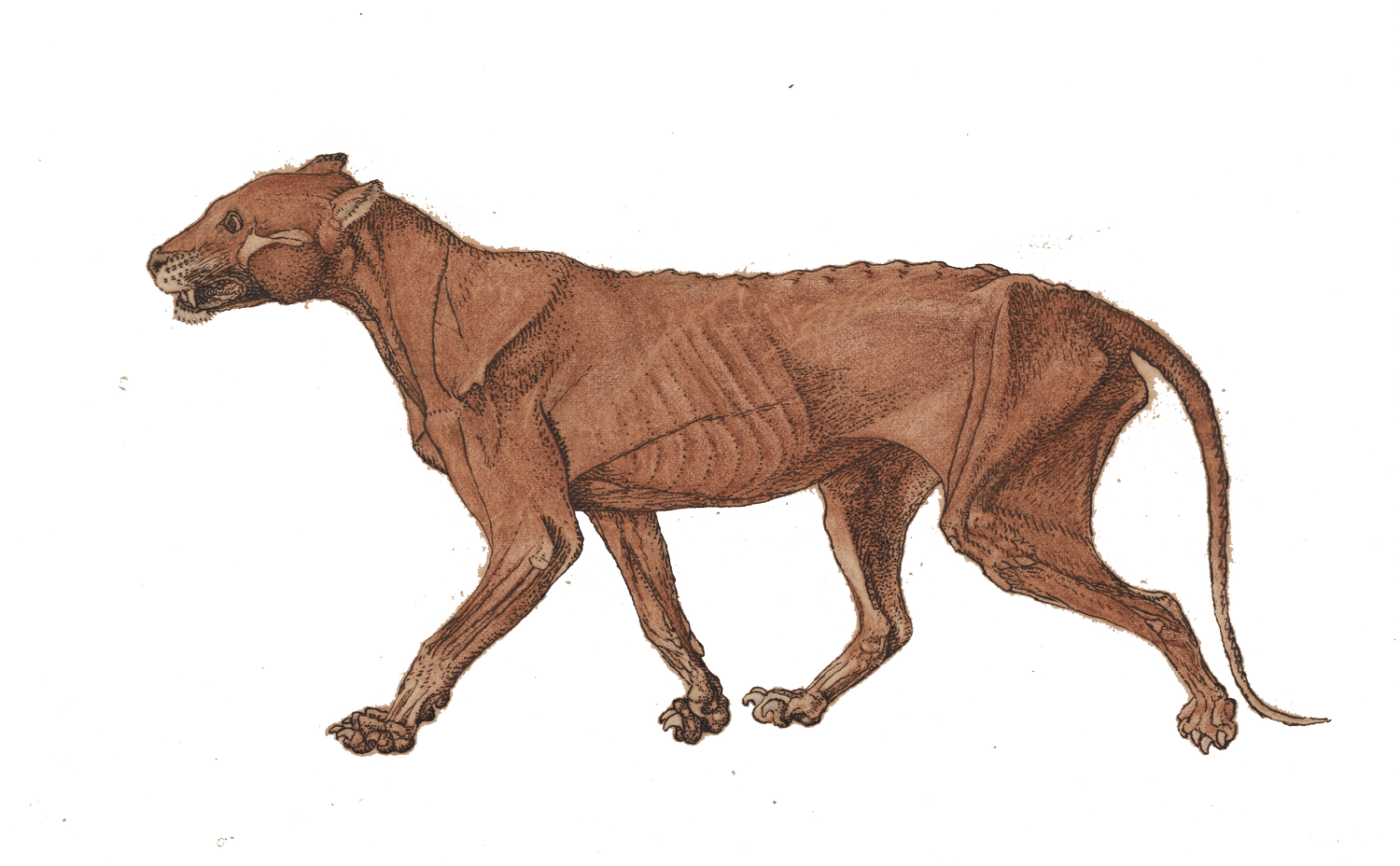

For instance, how might the tiny depiction of a tiger hunt in an international exhibition-inspired board game from Victorian England resonate with a contemporary installation that overlaps mythologies of the tiger to define Southeast Asian regionality? Henry Smith Evan’s The Crystal Palace Game maps the logic of the British Empire to promulgate imperialism through didactic play. But his mapping also reveals a path towards the formation of solidarity across India and Southeast Asia. Such potentiality is actualized in Ho Tzu Nyen’s One or Several Tigers. His work reimagines the tiger hunt motif beyond the artificial spatiotemporal limits of colonial India.

2 or 3 Tigers and One or Several Tigers layer video and multimedia imagery to destabilize imperial constructions of Southeast Asia. In the latter, Ho Tzu Nyen appropriates a German print of George Drumgoole Coleman, British surveyor and superintendent of public works in Singapore, and several convict laborers (who were forcibly displaced from India) amidst a tiger attack. Animated avatars of the tiger and Coleman sing to each other in a ritualistic exchange; their bodies metamorphosize as they evoke the complex allusive power of the Malayan tiger fragmented through Southeast Asia pluralistic histories. This digital postcolonial imaginary is powerful beyond Ho’s Singapore: “To track the tiger is to embark on a journey that has no respect for national boundaries.”

Ho Tzu Nyen. One of Several Tigers, 2017 and 2 or 3 Tigers, 2015.

Henry Smith Evans. The Crystal Palace Game: a voyage round the world, an entertaining excursion in search of knowledge, whereby geography is made easy, ca. 1854. Gift of Ellen and Arthur Liman, ’57 J.D. Yale Center for British Art

Photograph of a Residential Room at Yale, 1894. Historical Photos, Yale University Office of Public Affairs and Communications

The archive is an aspiration, not a recollection. It is a conscious site of debate and desire. It is a work of imagination.

Some 130 years ago, a student would have looked at himself in his dormitory room mirror, surrounded by objects that, however consciously, retained imperial traces in their mere material presence. The lines on this mirror are adapted from Arjun Appadurai’s essay “Archive & Aspiration.” Our presence at Yale implicates us in the university’s history of knowledge production. It renders us complicit in ignoring the vestiges of imperialism still alive on campus. How will you reimagine the archive?

In the physical display, an actual mirror, similar to the one in the above photograph, was hung at eye-level, with words overlaid on the glass.

Holly Shaffer. Adapting the Eye: An Archive of the British in India, 1770–1830, 2011.

Yale Center for British Art

The harmful ideologies enacted through the Empire’s visual culture can perhaps never be fully destroyed, especially in a museum dedicated to collecting and exhibiting British art. But it is precisely this focus that makes the Yale Center for British Art a powerful space to stage curatorial interventions. Holly Shaffer’s 2011 exhibition complicates long-suppressed histories of life in colonial India. Her attempt (and here, too, mine) to disrupt the archive, however, is only one beginning.