Shooting Tigers

Printed Potentialities

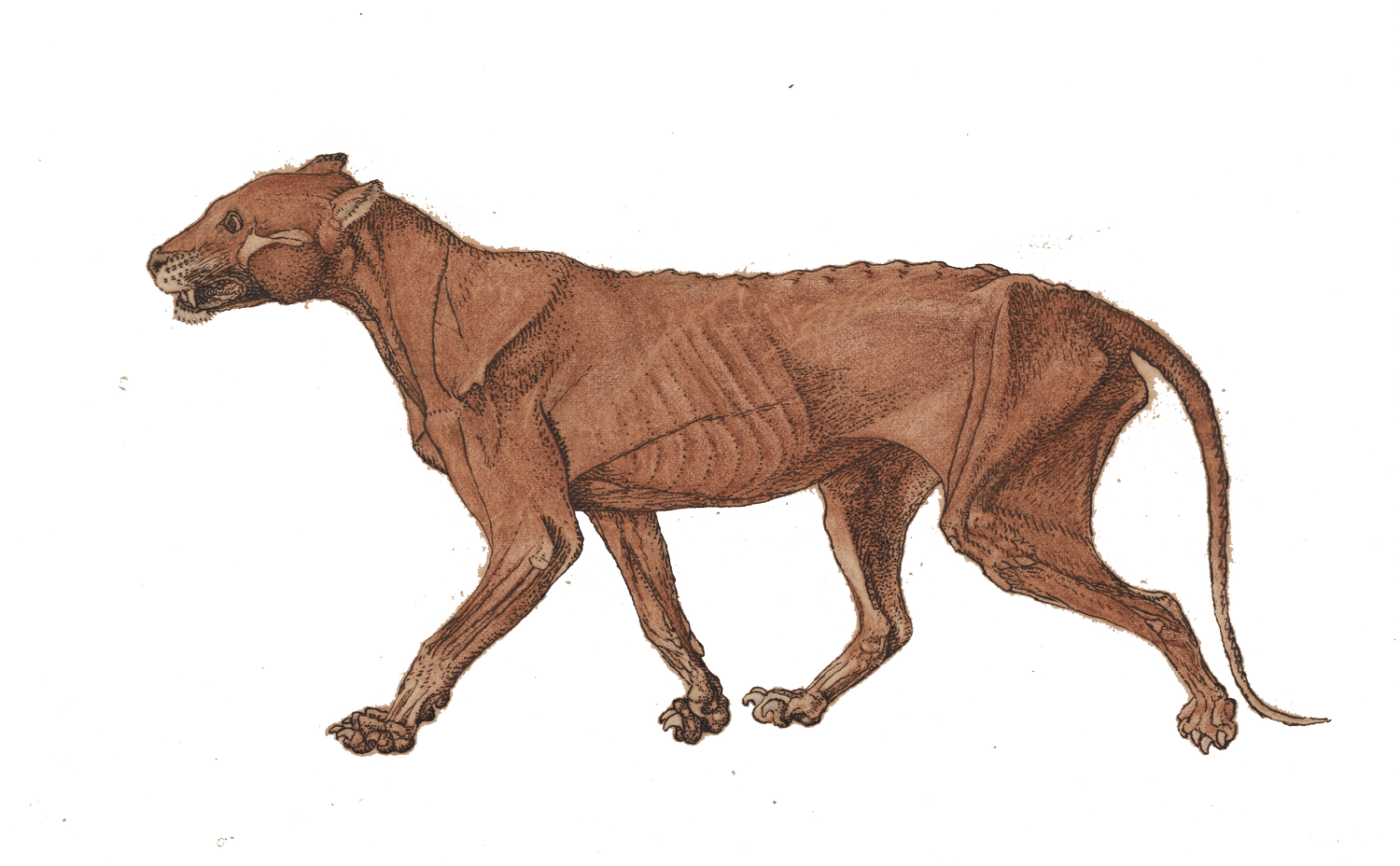

Tiger hunts proliferated in Britain through print. Such circulation enabled rapid reproductions of imperial power even as these redistributions inevitably spiraled beyond colonial control. The English viewer who accessed the tiger hunt through print never compromised his safety. In Britain, death by tiger was nearly impossible. Prints became a tactile means by which people were unified under the aegis of the empire. In D’Oyly’s lithographs, however, his printed beasts’s inaccurate anatomy makes one question whether he ever saw––let alone shot––a tiger.

Colonial hunters, too, minimized their risk by treating Indian laborers––whose skills were ironically essential to a successful hunt––as expendable. Locals bore the dangerous burden of tracking tigers on the ground. In print, they were depicted as animalistic, cowardly, or excluded entirely. D’Oyly’s lithograph Tiger Shooting enacts all three dehumanizing tactics. Crouched in a tree, the men’s postures echo the tiger’s. Their bodies dissolve into the vegetation.

Sir Charles D’Oyly. Tiger Shooting, in his album Indian Sports, 1828–9. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

Widespread global circulation meant that it was impossible for imperial performance to be uniformly maintained. Print’s endlessly reproducible nature denies the colonizer’s claims to individual ownership over objects and ideas. Such objects constantly change hands. Their meaning is re-appropriated and transformed with each new activation. While this made print a powerful tool of colonial propaganda, it also made print a medium of potential resistance. The emergence of photography in India after 1839 only introduced more complexity. The medium’s seemingly documentary nature enforced myths of colonial objectivity. Yet, the shifting relations between photographer and subject fundamental to the photographic process frustrated imperial hegemony.

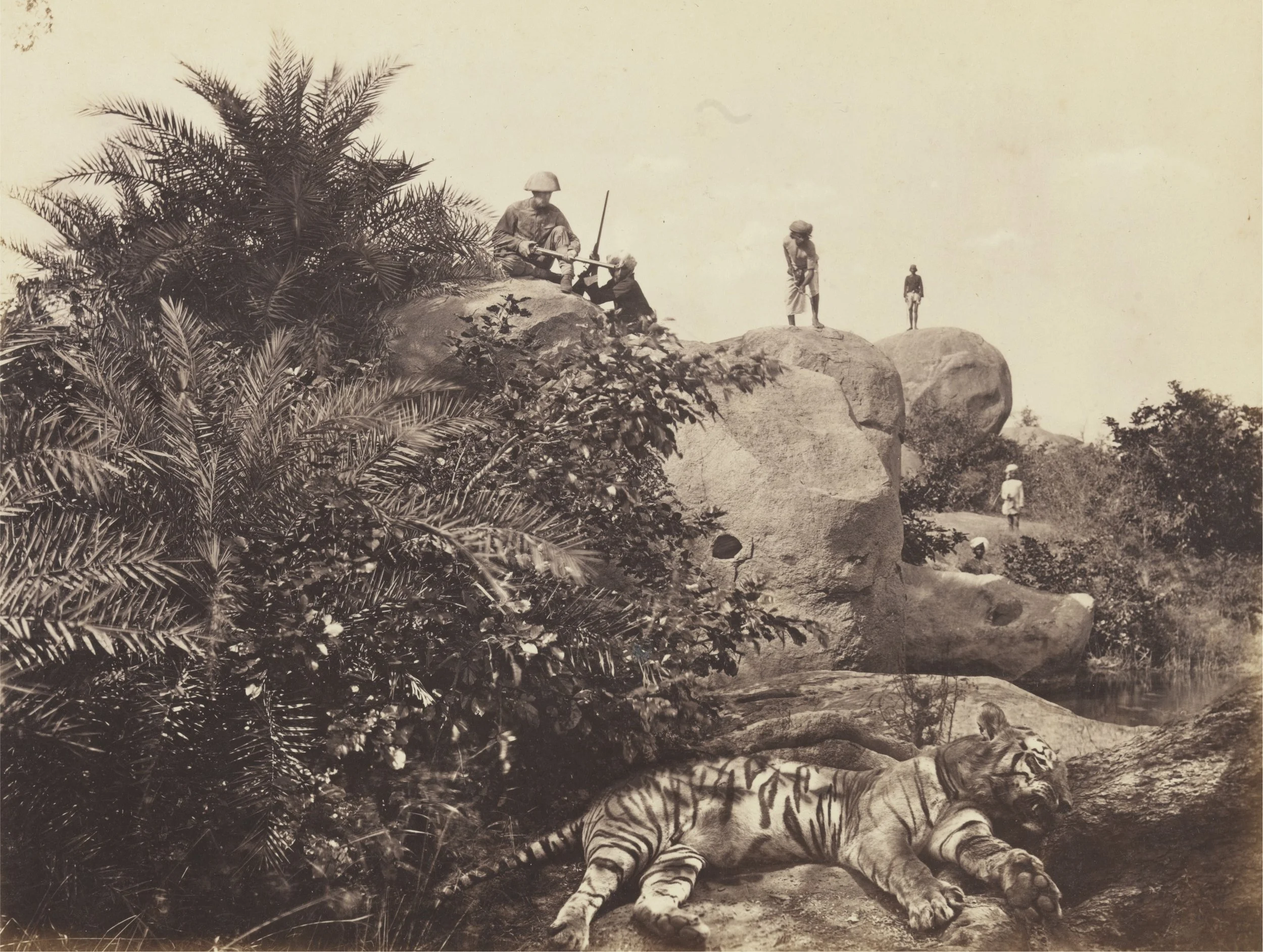

Willoughby Wallace Hooper. The Tiger Hunt: Bagged, ca. 1872. Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro, Yale Center for British Art

D’Oyly’s lithographs probably reached only a small viewing public in his lifetime. Their presence at Yale now opens potential for present critique. By contrast, Willoughby Wallace Hooper’s photograph The Tiger Hunt: Bagged was never afforded the same immobility. The men’s faces are blurry due to the long exposure time. This bears testament to their humanity as individuals whose moving bodies resist erasure within the landscape. Their unreadable expressions render the dynamic between hunter, photographer, and laborer ambiguous.

A retouched area just above the tiger’s back flank has also aged unevenly. Its cool grey, once colored to be indistinguishable from the rest of the photograph, now contrasts the faded warmer tones. The retouching underscores an inadvertent desire to prolong imperialism in the image beyond the empire’s waning. Time, however, has proven the attempt futile.

Just as the British appropriated Indian tradition for their colonial ends, the tiger hunt motif was adapted to enact imperial violence elsewhere. Following France’s defeat in the Battle of Leipzig, this illustration satirized Napoleon as a wounded tiger who leaps desperately into the Rhine to flee Alexander I of Russia, Francis I of Austria, Frederick William III of Prussia, and Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria’s coalition army.