Empire Dreaming

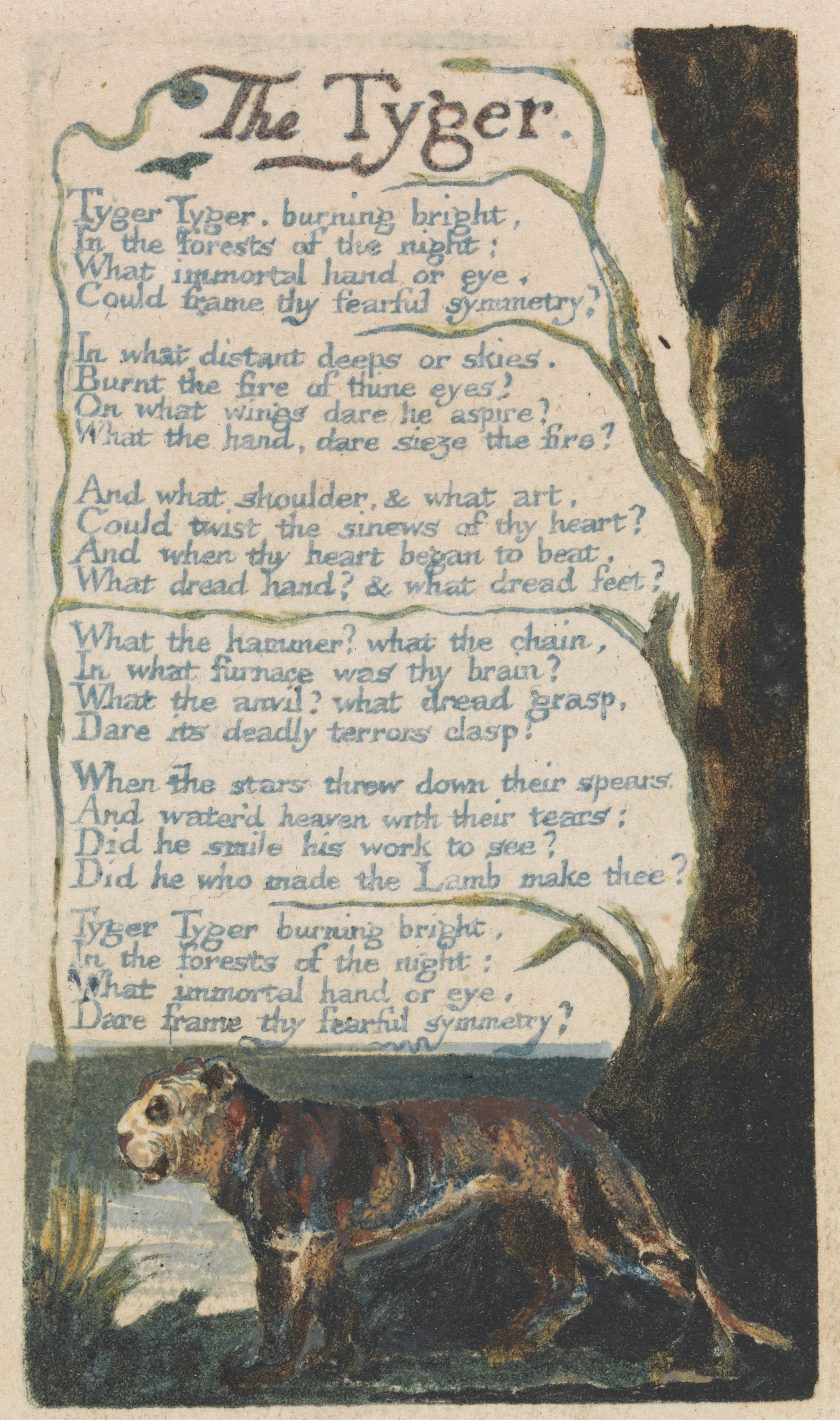

Blake was not alone in his fascination with the tiger. When “The Tyger” was published in 1794, the East India Company had been making forays into India for nearly two centuries. Tigers were often shipped to England as exotic souvenirs. Londoners could encounter these “man-eaters” at the Tower of London’s Royal Menagerie or in circuses and cockpits where one could place a wager on a tiger’s odds against other animals.

In Georgian England, the tiger was both an object of spectacle and––as Blake’s poem evokes––the very essence of a terrifying beast. They epitomized the animal kingdom’s threat to man, though this anthropocentric view ignores the fact that tigers only attack people when provoked or unnaturally dislocated. Treated as commodities, many tigers did not survive the passage from Asia to Europe. Tiger skins were used as rugs, their heads stuffed as ornaments. Those that did lived out distressed existences shortened by unsuitable habitation. Their bodies were likely then preserved or dissected in service of modern taxonomy and classification.

A new age of natural history had emerged in eighteenth-century Europe. No longer set apart from animals, humans became a subject of scientific study. The fearsome tiger, who could potentially destabilize man’s place in God’s hierarchy, increased anxieties around divine creation: “Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” By the early Victorian period, the British public were well-primed to enact domination through images of the tiger hunt.

Tigers in the British Enlightenment

William Blake. Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 42, "The Tyger" (Bentley 42), 1794. Paul Mellon Collection Yale Center for British Art

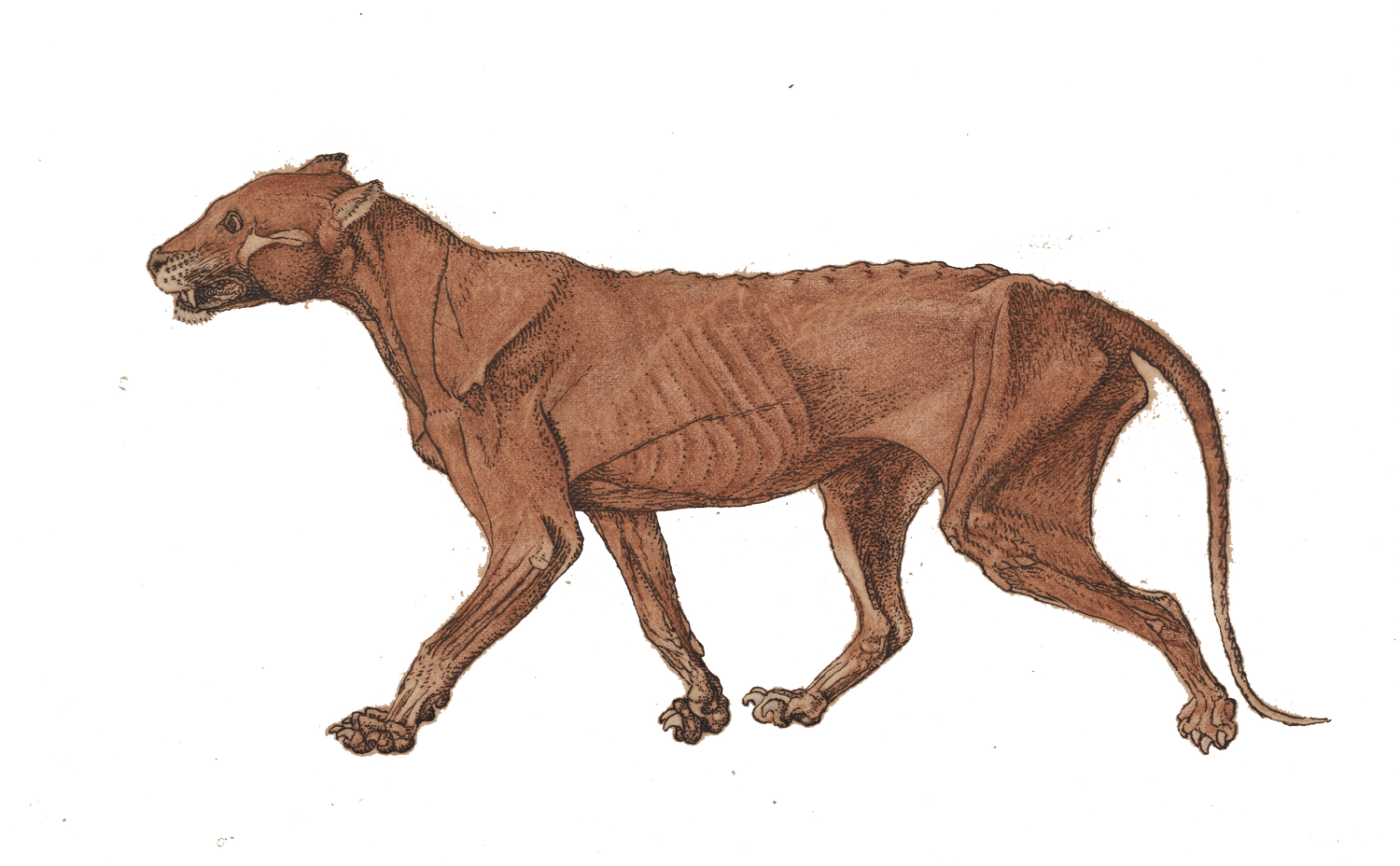

George Stubbs. Tiger Body, Lateral View, Skin Removed, ca. 1795–1806. Prints and Drawings, Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

George Stubbs. Tiger Body, Lateral View, Skin Removed (Diagram), ca. 1795–1806. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

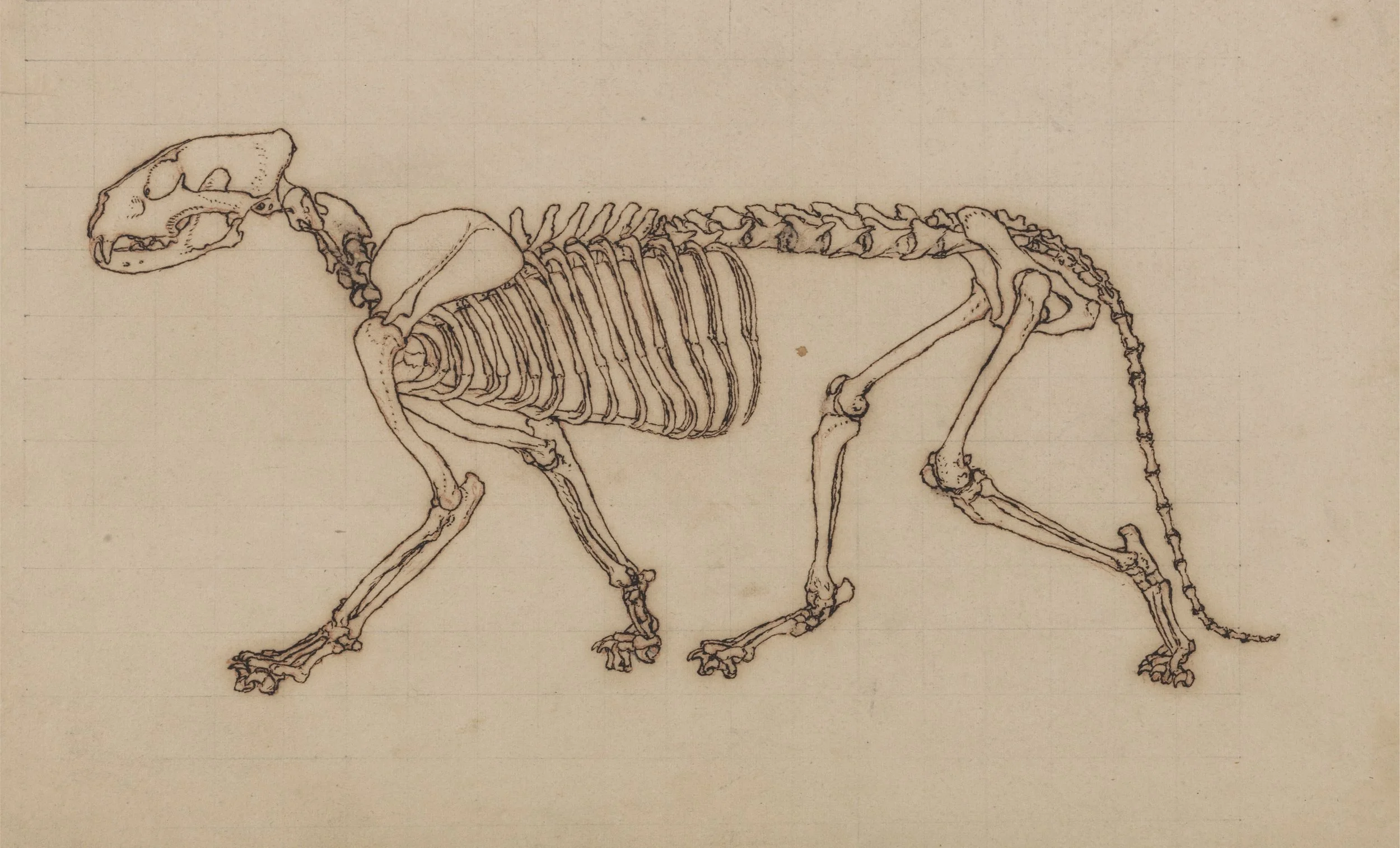

George Stubbs. Tiger Skeleton, Lateral View, ca. 1795–1806. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

Though mainly remembered today for his horse paintings, George Stubbs had a lifelong interest in anatomy. He commenced his swansong, A Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body with that of a Tiger and a Common Fowl, in 1795. Stubbs created 125 drawings to document each autopsy. He bought the dead tiger from Gilbert Pidcock’s traveling menagerie for three guineas. Its body is indexed through Stubbs’s systematic draftsmanship. Mastered by the logic of dissection, Pidcock’s tiger becomes an object of scientific analysis. As with all the tigers displaced from India to England, the tiger Stubbs drew was once a breathing animal that probably suffered mistreatment on and after its journey west.