Empire Actualized

Tiger Hunting in Colonial India

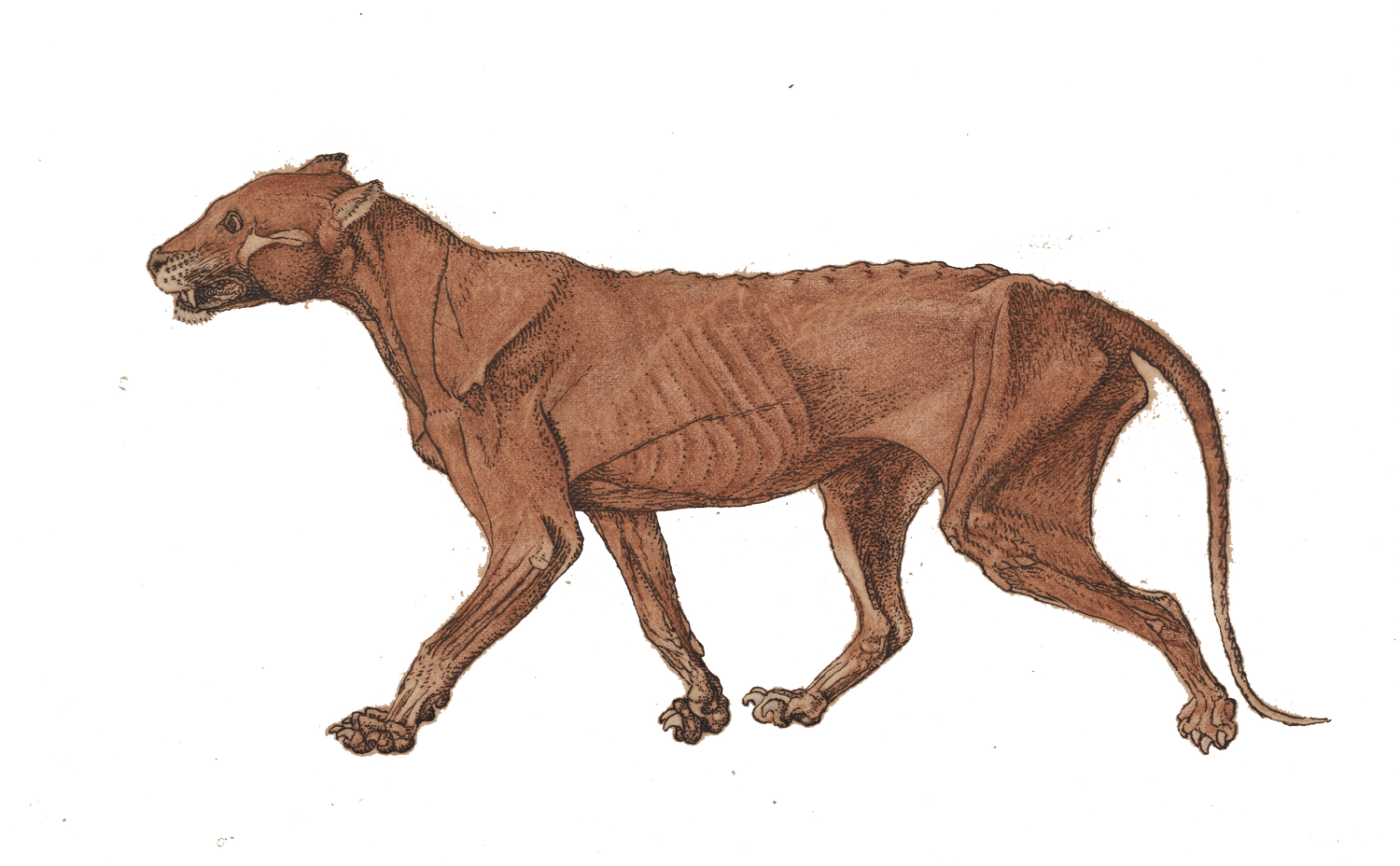

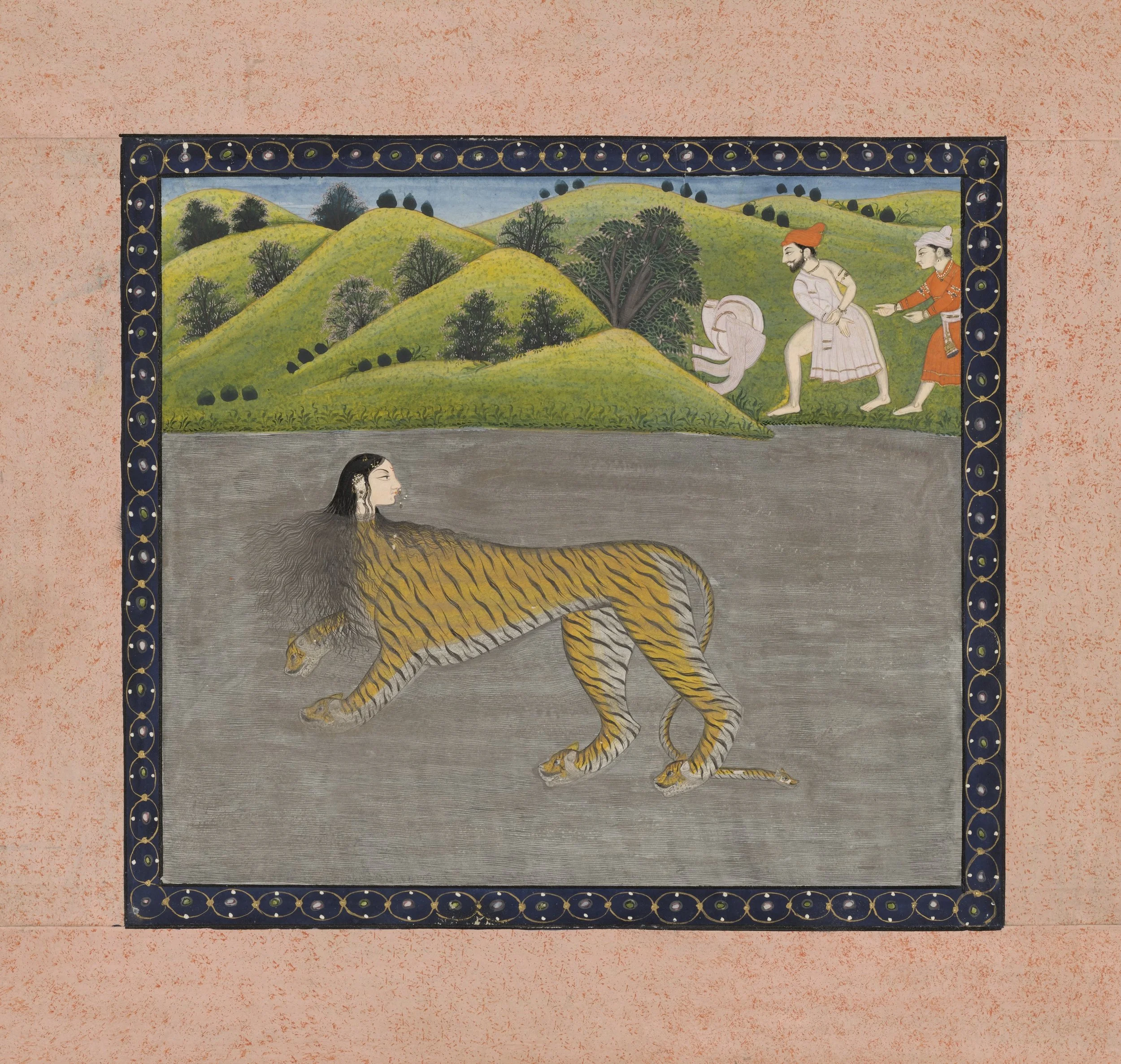

There existed a centuries-long history of tiger hunts amongst Indian royal dynasties: shikar (hunting) reflected courtly status and enabled territorial expansion. The Mughals used tiger hunts to prove their martial prowess and subjugate rebels. Still, many communities in India also believed in the ability of the human consciousness to merge with that of the tiger. The painting of a woman transforming into a tiger displayed here belongs to a long visual tradition of tiger-human hybrids. Though the gender dynamics within this painting render the metamorphosis more ambivalent, the tiger was generally respected as a spiritual equal.

Such a belief, however, did not align with the British desire to dominate India. To legitimize their authority, the British authorities appropriated the local significance of the hunt as a display of imperial might. Local communities were denied hunting rights. Tiger hunting became an exclusive privilege of the settler-colonialists.

But the British also associated tigers with the alleged savagery of Indians. The death of the tiger at the hands of an Englishman exemplified the colonizer’s retributive justice in subduing an unregenerate subject. Depictions of tiger hunts circulated in Britain reinforced narratives of the virtue and heroism of the Empire.

Unknown artist. Woman Transforming into a Tiger, ca. 1810–20. Katharine Ordway Collection. Yale University Art Gallery

Bhupal Singh. Emperor Muhammad Shah (1702–1748) Hunting, ca. early to mid-eighteenth century. The Vera M. and John D. MacDonald Collection, ’27, Gift of Mrs. John D. MacDonald

Sir John Tenniel. The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger, August 22, 1857. Punch, vol. 33, no. 1, August 22, 1857. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

The 1857 Indian Rebellion––known also as a war of independence––was a major uprising against the East India Company. Colonial control tightened after the unsuccessful revolt: India was placed under the British government’s direct rule.

Sir John Tenniel’s illustration, displayed to the left, incited English outrage. He positions the innocent white woman and her child as victims, the Indian tiger as a barbaric criminal, and the lion, symbolizing Britain, as a righteous avenger. Published in the popular periodical Punch, Tenniel’s cartoon underscored the need for the Englishman to protect his values and civilize the violent Indian subject. Such images emphasized a colonial career as noble and desirable. They attracted new colonists to India to perpetuate the imperial enterprise.