Domesticating the Tiger

Once slain, the fearsome tiger could safely be integrated into the domestic sphere. Tiger skin rugs adorned many colonial homes. As decorative centerpieces within rooms of leisure, these hunting trophies served as a visceral testament to the control the British had over both “man-eaters” and “restive human subordinates” in India. They asserted the power of the Englishman as defined against a subjugated other. What was death but the most absolute form of domination?

Tiger fur, however, was not the only thing the British acquired in India for aesthetic ends. Looted spoils were transported back to England by the crateful. Objects ranging from ancient coins to devotional statues ended up in private collections of the wealthy, or on display in London’s international fairs like the Great Exhibition of 1851.

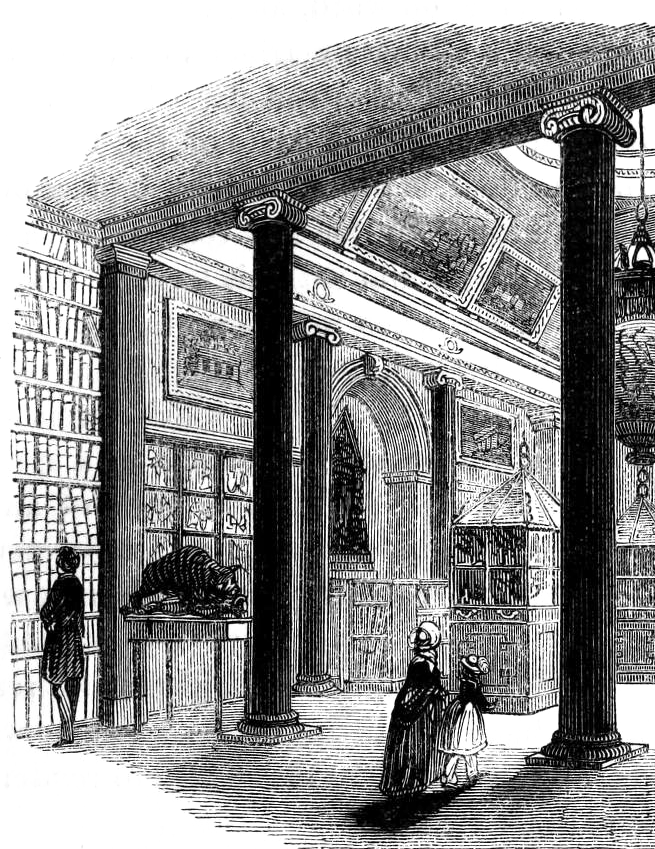

The access Victorians had to encyclopedic museums as affordable sites of recreation is significant. Intended to instruct and enlighten, the display of plundered artifacts materialized even the most far flung of colonies within a single space. All ends of the Empire became transparent, accessible, and governable for the British viewer. Museum collections functioned as didactic imperial archives, part of a global capture of knowledge that was activated by the English as an apparatus of control. In these archives, access to information is normalized as the colonizer’s superior right. Such access decontextualizes and asserts his ownership over objects, territories, and ideas that were, in reality, never his.

Imperial Archives

Charles Knight. Illustration of Tippo’s Tiger in the East India House, 1843. London Pictorially Illustrated, vol. 5, 1843

Joseph Constantine Stadler, after Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. East India House in London, ca. 1780–1812. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

Sir Charles D’Oyly was a lifelong East India Company employee. He was also an amateur artist whose paintings, seen below hanging in his summer room at Patna, identify him as both imperial creator and collector. Only the landscape and an Indian servant’s presence beyond the threshold indicate the tropical setting––tiger skins were by this time naturalized into the metropole’s interiors.

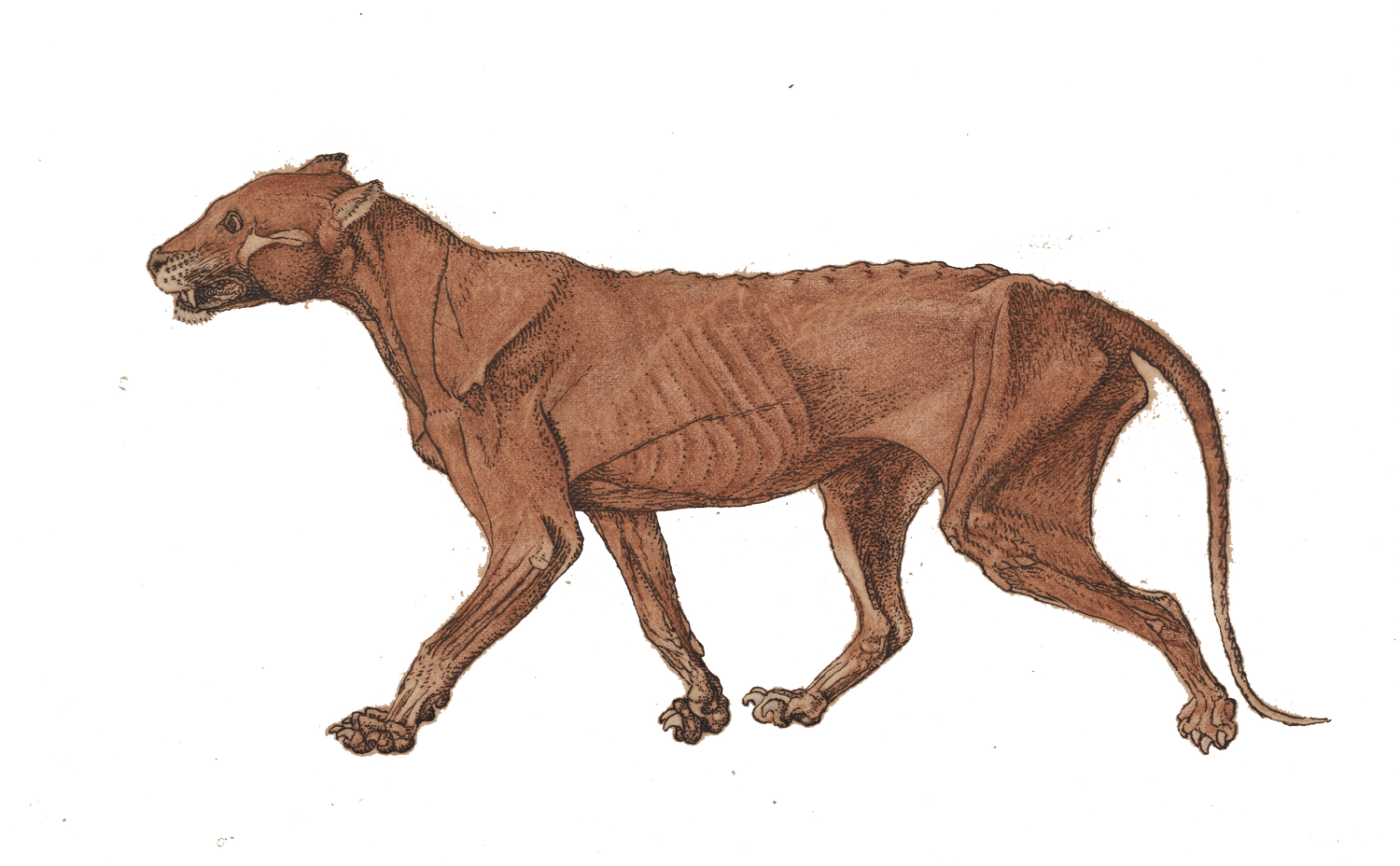

Another displaced spoil was Tippoo’s Tiger. The sultan of Mysore in Southern India, Tipu Sultan’s self-fashioning as “The Tiger of Mysore” and his resistance to British expansion with French allies engendered exceptional vitriol. An organ, Tippoo’s Tiger shrieks when cranked, befitting its depiction of a tiger mauling an Englishman. Looted after Tipu’s defeat and as illustrated on the leftmost table within Knight’s print, the instrument stood in the East India House alongside “Oriental curiosities” like ivory-lanterns and stuffed Javanese birds, exemplifying British triumph.

Sir Charles D’Oyly. The Summer Room in the Artist’s House at Patna, September 11, 1824. Paul Mellon Collection

Yale Center for British Art

T. Charles Erickson. Long Gallery, May 1983. Yale University Office of Public Information

It bears remembering that a source of Elihu Yale’s wealth was the East India Company’s subjugation of enslaved peoples. So implicated through the university’s primary benefactor, the preservation of images of tiger hunting in Yale’s collections perpetuates the imperial archive. Yale’s museums, too, descend from a lineage of private collections. These legitimized ownership of extractive plunder and Eurocentric cultural hierarchies. The performance of power persists.